Along the River Ran Along the River Ran

Fragment d'un film à venir

Film Super-8, N&B, 3 min, 2019

Fragment d'un film à venir

Film Super-8, N&B, 3 min, 2019

Fragment d'un film à venir

Film Super-8, N&B, 3 min, 2019

Fragment d'un film à venir

Film Super-8, N&B, 3 min, 2019

Le 10 août 1936, James Joyce écrivait une lettre à son petit-fils, Steven. Il y est question de la ville de Beaugency, d’un pont et de celui qui devait le construire : le diable…

Le 10 août 1936, James Joyce écrivait une lettre à son petit-fils, Steven. Il y est question de la ville de Beaugency, d’un pont et de celui qui devait le construire : le diable…

Vers cette neige, vers cette nuit (Extrait 1)Towards This Snow, Towards This Night (Excerpt 1)

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur et N&B, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

Avec : Olga Lukasheva

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

With : Olga Lukasheva

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur et N&B, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

Avec : Olga Lukasheva

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

With : Olga Lukasheva

Une histoire d’amour entre textes, images et sons.

Un scénario - celui d’un homme qui laisse des messages à une femme qui ne répond jamais - vient interrompre sous forme d’intertitres le défilement d’images provenant de bobines super-huit qui auraient été perdues et retrouvées. Et, comme en écho, la présence d’enregistrements sonores, peut-être eux-mêmes perdus et retrouvés. Sur les images : une chambre, un appartement, des rues, des ponts, des passants, une flânerie dans une grande ville, Saint-Petersbourg, en Russie. Sur les bandes sonores, les bruits de la ville, celui du métro, de la rue et de chants orthodoxes.

Le titre provient d’une phrase de la poète russe Olga Bergholtz : « Ne retourne pas là-bas, vers cette neige, vers cette nuit, le regard de quelqu’un t’attend. »

Ce film, pensé selon le motif du fragment, prolonge un large projet consacré aux ponts en tant qu’ils sont une possible représentation architecturale du langage comme lien qui sépare. Il fait suite au film L’invitation au voyage.

A love story amid texts, images and sounds.

A script – about a man who leaves messages to a woman who never answers – applies captions to interrupt the stream of images taken from Super-8 film reels that were allegedly lost and then found again. An echo effect is created by the presence of sound recordings, which were perhaps also lost and found. Re the images: a bedroom, an apartment, streets, bridges, passersby, meandering through a Russian city, Saint-Petersburg. Re the soundtrack: city-noises, the subway, the street, Orthodox chants.

The title is borrowed from a line by the Russian poet Olga Bergholtz: “Don’t go back there, towards this snow, towards this night, the gaze of someone who awaits you.”

The film is underscored by the motif of fragmentation, and pursues a broader project on bridges, which can architecturally represent language as a bond that separates. The project was launched with the film Invitation to a voyage.

Vers cette neige, vers cette nuit (Extrait 2)Towards This Snow, Towards This Night (Excerpt 2)

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur et N&B, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

Avec : Olga Lukasheva

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

With : Olga Lukasheva

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur et N&B, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

Avec : Olga Lukasheva

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 16/9, 47 min, 2017

With : Olga Lukasheva

Une histoire d’amour entre textes, images et sons.

Un scénario - celui d’un homme qui laisse des messages à une femme qui ne répond jamais - vient interrompre sous forme d’intertitres le défilement d’images provenant de bobines super-huit qui auraient été perdues et retrouvées. Et, comme en écho, la présence d’enregistrements sonores, peut-être eux-mêmes perdus et retrouvés. Sur les images : une chambre, un appartement, des rues, des ponts, des passants, une flânerie dans une grande ville, Saint-Petersbourg, en Russie. Sur les bandes sonores, les bruits de la ville, celui du métro, de la rue et de chants orthodoxes.

Le titre provient d’une phrase de la poète russe Olga Bergholtz : « Ne retourne pas là-bas, vers cette neige, vers cette nuit, le regard de quelqu’un t’attend. »

Ce film, pensé selon le motif du fragment, prolonge un large projet consacré aux ponts en tant qu’ils sont une possible représentation architecturale du langage comme lien qui sépare. Il fait suite au film L’invitation au voyage.

A love story amid texts, images and sounds.

A script – about a man who leaves messages to a woman who never answers – applies captions to interrupt the stream of images taken from Super-8 film reels that were allegedly lost and then found again. An echo effect is created by the presence of sound recordings, which were perhaps also lost and found. Re the images: a bedroom, an apartment, streets, bridges, passersby, meandering through a Russian city, Saint-Petersburg. Re the soundtrack: city-noises, the subway, the street, Orthodox chants.

The title is borrowed from a line by the Russian poet Olga Bergholtz: “Don’t go back there, towards this snow, towards this night, the gaze of someone who awaits you.”

The film is underscored by the motif of fragmentation, and pursues a broader project on bridges, which can architecturally represent language as a bond that separates. The project was launched with the film Invitation to a voyage.

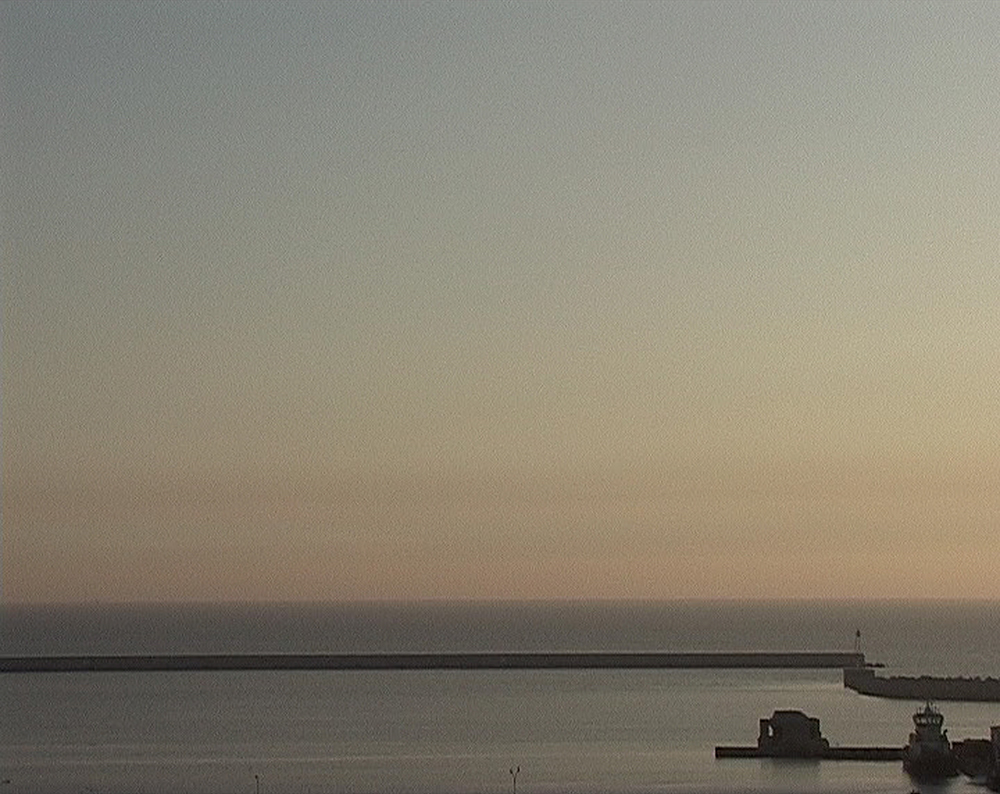

L'invitation au voyageInvitation to a Journey

Film HDV, Couleur, 33 min, 2013

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Marseille-Provence 2013 ; FRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur ; Ville de Martigues

HDV film, Color, 33 min, 2013

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Marseille-Provence 2013 ; FRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur ; Ville de Martigues

Film HDV, Couleur, 33 min, 2013

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Marseille-Provence 2013 ; FRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur ; Ville de Martigues

HDV film, Color, 33 min, 2013

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Marseille-Provence 2013 ; FRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur ; Ville de Martigues

Dans le poste de commandement – unique décor du film – qui surplombe le pont levant de la ville de Martigues, au rythme des passages de bateaux, un homme raconte l'histoire d'un certain Thomas, qui décida d'apprendre le persan auprès d'un mystérieux capitaine. Après un long apprentissage, convaincu de maitriser suffisamment la langue persane, il décida d'écrire son propre texte, avant de découvrir que cette langue qu'il croyait avoir apprise n'existait nulle part. Le pont devenant une possible représentation architecturale et symbolique du langage comme lien qui sépare.

At a command post – the film’s sole setting – which overlooks the lift bridge of the town Martigues against the backdrop of passing boats, a man tells the story of a certain Thomas, who decided to learn Persian from a mysterious captain. After a long apprenticeship, by now convinced that he has reached sufficient mastery, Thomas ventures to write a text of his own, at which point he discovers that the language he’d ostensibly been learning is nonexistent. The bridge turns into an architectural and symbolic representation of language as a bond that separates.

Fragments de vie d'un club de boxeGlimpses of a Boxing Club

Film HDV, Couleur, 23 min, 2010

Production : CRAC Le 19

HDV film, Color, 23 min, 2010

Production : CRAC Le 19

Film HDV, Couleur, 23 min, 2010

Production : CRAC Le 19

HDV film, Color, 23 min, 2010

Production : CRAC Le 19

Pendant près d’un an furent filmés les entraînements du club de boxe du quartier de la Petite Hollande de Montbéliard. Adultes et enfants, débutants ou confirmés, répètent les mêmes gestes, affinent leurs styles et développent leurs conditions physiques. Séances de sac de frappe, simulation de combats, apprentissage de nouveaux coups et de nouvelles parades, combats. Au-delà de la boxe, c’est le sport comme rituel qui devient sujet.

Over the span of a year or so, training sessions were filmed at a boxing club in the Petite Hollande district of Montbéliard. Adults and children, whether beginners or advanced, repeat the same motions, honing their style and developing physical prowess. Boxing bag workouts, combat simulations, lessons in new punches, new moves and fight techniques. Beyond boxing, it’s all about sport as ritual.

Au fil de l'oubliThe Path of Oblivion

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 23 min, 2009

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Co-production : École Supérieure d’art et de design Marseille-Méditerranée

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 23 min, 2009

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Co-production : École Supérieure d’art et de design Marseille-Méditerranée

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 23 min, 2009

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Co-production : École Supérieure d’art et de design Marseille-Méditerranée

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 23 min, 2009

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Co-production : École Supérieure d’art et de design Marseille-Méditerranée

Sur la digue du grand large (également appelée « Jetée de l’oubli ») du port autonome de Marseille, là où les bateaux restent longuement à quai, plusieurs inscriptions laissées par les marins s’y lisent. Parmi elles, trois idéogrammes chinois. Au fil des recherches, se tisse l’histoire d’un navire taïwanais dont le nom inscrit sur un registre de marine est l’objet de diverses conjectures.

At Marseille’s open-sea port (also called “pier of oblivion”), where ships remain docked for long periods, one comes across inscriptions left by sailors, including three Chinese ideograms. Along the path of inquiry, a tale is woven about a Taiwanese ship, which, being listed in a marine registry, has given rise to various conjectures.

The study (Cabinet d'étude)The Study

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur, 11 min, 2009

Voix : Nicky Dingwall-Main

Production : Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Maison Dora Maar, Ménerbes

Super-8 film digitized, Color, 11 min, 2009

Voice : Nicky Dingwall-Main

Production : Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Maison Dora Maar, Ménerbes

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur, 11 min, 2009

Voix : Nicky Dingwall-Main

Production : Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Maison Dora Maar, Ménerbes

Super-8 film digitized, Color, 11 min, 2009

Voice : Nicky Dingwall-Main

Production : Museum of Fine Arts, Houston ; Maison Dora Maar, Ménerbes

C’est l’histoire d’une expérience pratiquée sur le cadavre d’un jeune condamné à mort par guillotine. Sur la rétine de l’oeil gauche se révèle une image qualifiée de « distincte mais ambiguë ». Le film met en scène ce récit sous forme d’intertitres entrecoupés de plusieurs séries d’images vues à la visionneuse optique super-8, dont le rythme de défilement rappelle des clignements d’yeux. Les images sont sans relation apparente avec l’expérience décrite. Une voix de femme, off, dit le souvenir du texte écrit, concomitamment aux intertitres et images créant une étrange polysémie.

Le récit de cette expérience s’inspire des recherches photos-optiques portant sur l’optogramme, obtenues par le physiologiste allemand Wilhelm Kühne, ainsi que par le Docteur Auguste Gabriel Maxime Vernois. qui fit paraître, dans la Revue photographique des hôpitaux de Paris, un article titré Étude photographique sur la rétine des sujets assassinés (1870).

The story of an experiment conducted on the corpse of a young man condemned to die by guillotine. The left eye’s retina revealed an image that was deemed “precise yet ambiguous”. The film enacts this incident by way of captions interspersed with series of images seen through a Super-8 viewer, to a rhythm that resembles blinking. The images bear no apparent relationship to the experiment. A female voice-over reminisces about the written text while the captions and images are screened, thereby creating a strange polysemy. The account of this experiment draws inspiration from photo-optical research on the optogram carried out by the German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne as well as by Dr. Auguste Gabriel Maxime Vernois, who had published an article in the medical photo-journal of the Hospitals of Paris entitled Étude photographique sur la rétine des sujets assassinés (1870).

L'ombre d'un échoShadow of an Echo

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B et Couleur, 13 min, 2007

Lectrice : Rosa Borges

Danseuses : Marine Brothier-Macarios, Marion Jacquemet

Musique : Jean-Michel Pirollet

Coproduction : Cité des Arts, Chambéry

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 13 min, 2007

Reader : Rosa Borges

Dancers : Marine Brothier-Macarios, Marion Jacquemet

Music : Jean-Michel Pirollet

Coproduction : Cité des Arts, Chambéry

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B et Couleur, 13 min, 2007

Lectrice : Rosa Borges

Danseuses : Marine Brothier-Macarios, Marion Jacquemet

Musique : Jean-Michel Pirollet

Coproduction : Cité des Arts, Chambéry

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 13 min, 2007

Reader : Rosa Borges

Dancers : Marine Brothier-Macarios, Marion Jacquemet

Music : Jean-Michel Pirollet

Coproduction : Cité des Arts, Chambéry

Deux jeunes femmes (danseuses) découvrent par le toucher l’étui d’un instrument de musique ouvert, baillant, vide, avec en creux la forme de l’instrument vacant. Le souvenir de cette expérience tactile a donné lieu à un discours. Ce discours a été retranscrit en braille et soumis à la lecture d’une jeune femme, non-voyante. Le film articule le passage des mains découvrant l’étui à celles lisant le texte en braille. En fond sonore : quelques amorces de phrases musicales (jouées au saxophone).

Two young women (professional dancers), discover by the use of their hands, the open, gaping, empty surface of a musical instrument case, and the hollow form of its vacant instrument. The recollection of this tactile experience gave way to a speech, which in turn was transcribed in Braille and then read by a young, blind woman. The film articulates itself around the moment when the hands explore the case, to the voice of the young, blind woman reading the text in Braille. The background music consists of the stuttering ejaculations of a musical score (played by a saxophone).

Avant que ne se fixe

Before it Sets

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B, 17 min, 2007

Actrice : Masha Khokhlova

Musique : Louis Sclavis

D’après le livre d’Eric Suchère, "Fixe, désole en hiver"

Super-8 film digitized, Black-and-white, 17 min, 2007

Actress : Masha Khokhlova

Music : Louis Sclavis

Based on the book by Eric Suchère, "Fixe, désole en hiver"

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B, 17 min, 2007

Actrice : Masha Khokhlova

Musique : Louis Sclavis

D’après le livre d’Eric Suchère, "Fixe, désole en hiver"

Super-8 film digitized, Black-and-white, 17 min, 2007

Actress : Masha Khokhlova

Music : Louis Sclavis

Based on the book by Eric Suchère, "Fixe, désole en hiver"

Du livre d’Eric Suchère, « Fixe, désole en hiver », le film retient d’abord une silhouette de femme, de dos, en contre-jour, face à la mer au loin et aux collines à l’horizon. C’est une élégie, celle d’un motif dont mot et image fixent le déni, un motif que mot et image « illuminent de reflets réciproques ». À cela s’ajoute une bande son faite de bruits divers (train, vent, mer, pas dans la neige, respiration, pluie,…) autonome en apparence : un « ça ne colle pas » là pour renforcer la désespérée tentative de fixation par laquelle le film s’élabore.

An elegy of a motif, constructed out of words, images and sounds, brought to light in Eric Suchère's book, "Fixe, désole en hiver". A train journey in search of a woman's silhouette, seen against the light, her back to us, facing the distant sea and hills on the horizon.

Zagreb, répétitionZagreb, Repetition

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B et Couleur, 17 min, 2007

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 17 min, 2007

Music : Louis Sclavis

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B et Couleur, 17 min, 2007

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 17 min, 2007

Music : Louis Sclavis

Il s’agit initialement d’une expérience sur « l’oeil et la mémoire » proposée à des candidats volontaires, et consistant, dans un premier temps, en la présentation d’un court film. Puis il est demandé aux candidats d’exposer ce dont ils se souviennent. Le cas échéant, des photos extraites du film, à classer chronologiquement, leur sont présentées. L’un d’eux, après avoir reconnu le lieu filmé, se rappelle un traumatisme personnel : une alerte vécue de nuit pendant la guerre en ex-Yougoslavie. Le film scrute la relation, perceptuelle et mnémonique, qu’un spectateur entretient avec des images filmiques et photographiques.

Initially an experiment about ‘the eye and memory’, calling on volunteers and initially consisting of a presentation of a short film.

Secondly, the volunteers were asked to present what they remembered about the film. If necessary, photos taken of the film were presented to them and classified in a chronological order. One of the volunteers, after recognising the place where the film was shot, remembered a personal trauma, an alert experienced one night during the war in ex-Yugoslavia.

À une passanteTo a Passer by

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B, 10 min, 2005

Super-8 film digitized, Black-and-white, 10 min, 2005

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B, 10 min, 2005

Super-8 film digitized, Black-and-white, 10 min, 2005

Une image fixe, noire et blanche, pareille à une archive, est décrite par une jeune femme dont on entend la voix, seule.

Progressivement, la description, alors fidèle à l’image, se disjoint d’elle, met en scène un hors champ, devient récit. Puis la voix s’interrompt et l’image fixe se met en mouvement…

Le film s’inspire du TAT (Thematic Apperception Test), test de psychanalyse projective confrontant un patient à une série d’images et à qui il est demandé, pour chaque image, d’imaginer une histoire.

A film-still is exposed to the gaze of a young woman, she knows nothing about the film's origin or history, she simply comments on this singular, frozen-frame. Progressively her speech escapes her, taking on a new direction. This is an 'out-of-frame' story, a meander within an image and then into a film, a nomadic stroll through the city. The film was inspired by the TAT (Thematic Apperception Test), a projective psychoanalysis test, in which patients are confronted by a series of images and from which they are asked to imagine a story.

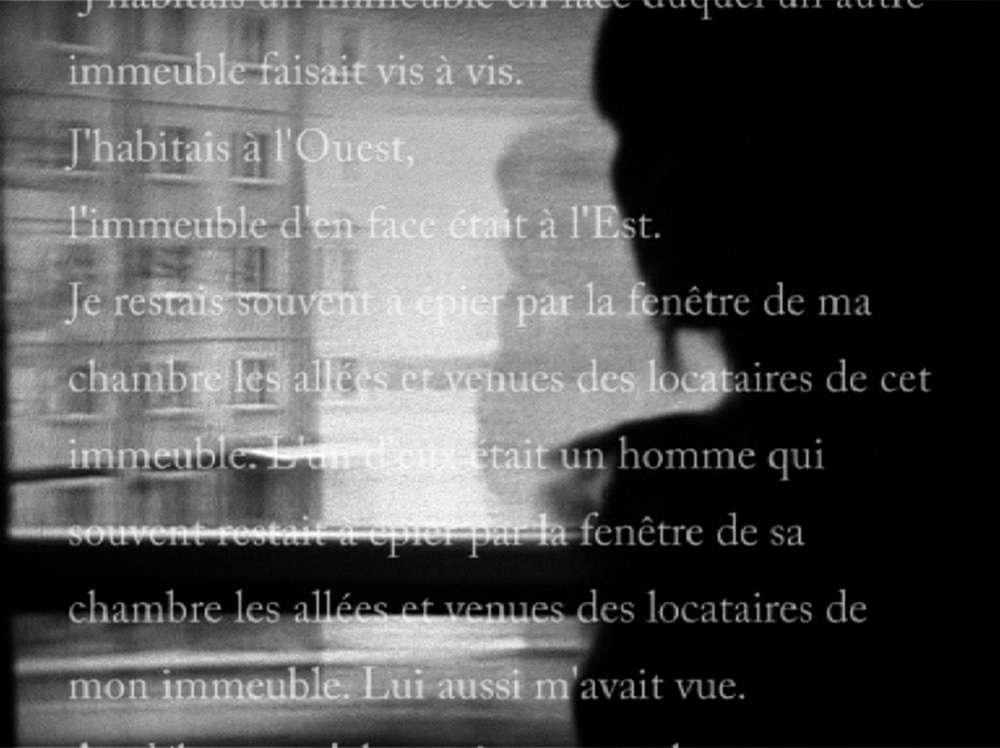

Berlin : traverséeBerlin : Crossing

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B et Couleur, 10 min, 2005

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 10 min, 2005

Film Super-8 numérisé, N&B et Couleur, 10 min, 2005

Super-8 film digitized, Color and black-and-white, 10 min, 2005

Un paysage rural défile, puis des immeubles, des rues. Berlin défile comme un décor, en une progression apparemment sans but. Arrive un texte, inscrit en caractères blancs, défilant de bas en haut : l’histoire d’une femme, la narratrice, qui vécut à l’ouest et communiqua par gestes avec un homme habitant juste en face, mais à l’est, de l’autre côté du mur…

A landscape passes by, filmed in Super 8, the image vacillates between black and white and colour, revealing streets and then buildings. The setting, Berlin. The film, a meander in what seems to be an aimless progression, with no preestablished route and moving in fits and starts. A text appears, inscribed in white lettering, it scrolls upwards; it tells the story of a narrator, who, living in the west of Berlin, communicated using bodily gestures to a man living opposite, but whose building was situated in the east, on the other side of the wall. A formal counterpoint to the Super 8’s logorrhoea, both text and image act against each other; the text becomes an obstacle, passing in front of the image like a wall, it induces the spectator’s imagination.

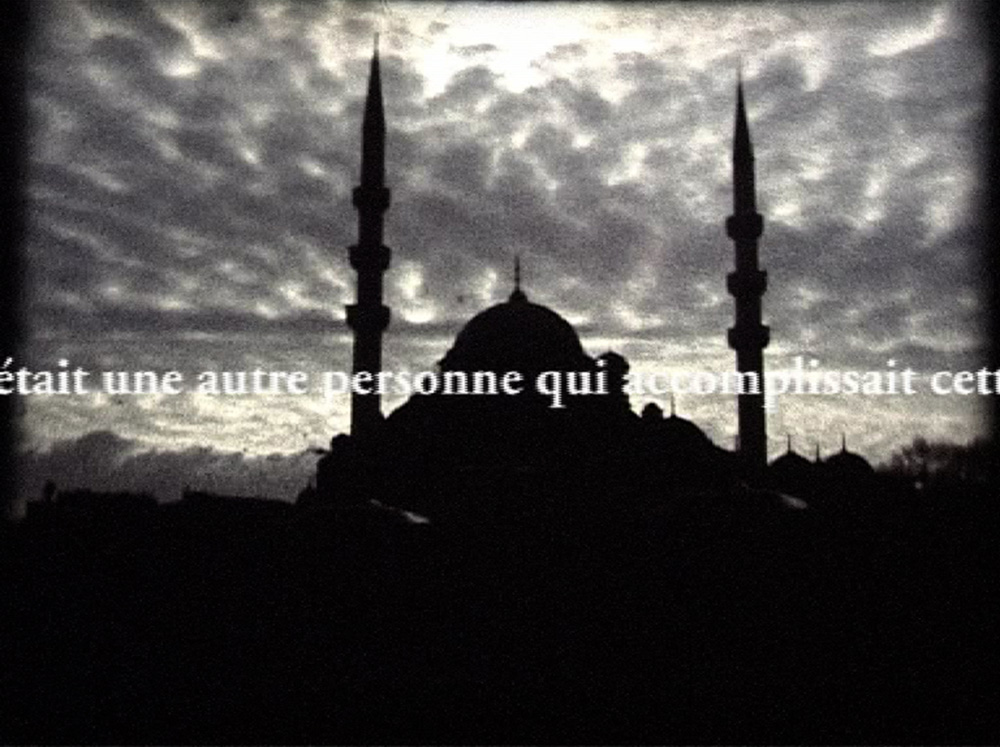

Istanbul, le 15 nov. 2003ISTANBUL, NOVEMBER 15th, 2003

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur, 12 min, 2004

Super-8 film digitized, Color, 12 min, 2004

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur, 12 min, 2004

Super-8 film digitized, Color, 12 min, 2004

Compte-rendu d’une hypothétique rencontre avec un ancien réalisateur turc, le 15 Novembre 2003, à Istanbul. Tout en projetant quatre de ses films super-huit, il raconte la ville, explique ses débuts dans le cinéma, comment il apprit le français. Il évoque une tour sur laquelle d’innombrables messages étaient inscrits dans toutes les langues et révèle l’existence d’un cinquième film…

An account of a hypothetical encounter with a former Turkish film director in Istanbul, November 15th, 2003. While projecting four of his super-8 films he tells the story of his city, explains his beginnings in cinema, how he learnt to speak French. He makes reference to a tower on which countless messages in every language were inscribed and reveals the existence of a fifth film...

Paris : 02 / 2003Paris : 02 / 2003

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur, 7 min, 2003

Super-8 film digitized, Color, 7 min, 2003

Film Super-8 numérisé, Couleur, 7 min, 2003

Super-8 film digitized, Color, 7 min, 2003

Errance parisienne sous forme d’expérience basée sur l’articulation cinématographique minimale, en tant que celle-ci ne s’opère pas entre les plans mais entre les images (selon la théorie de Peter Kubelka). Le film oscille entre prise de vue isolée et séquences fluides, soit la caméra utilisée comme un appareil photographique puis reprenant l’usage lui étant traditionnellement assigné : fixer du mouvement, du moins son illusion.

An experiment into cinematographic narration and its most minimal structure: the photogram (according to the theory of Peter Kubelka). The film attempts, via a series of projected images, to recreate a rythmic meandering through the city of Paris.

Les photos inductrices (Première partie)Inductive Photos (Part One)

Création de Louis Sclavis et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film HDV, N&B, 22 min, 2011

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 et LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création by Louis Sclavis and Fabrice Lauterjung

HDV Film, black-and-white, 22 min, 2011

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 and LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création de Louis Sclavis et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film HDV, N&B, 22 min, 2011

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 et LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création by Louis Sclavis and Fabrice Lauterjung

HDV Film, black-and-white, 22 min, 2011

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 and LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Le film est construit de trois couches narratives opérant en palimpseste.

Tout commence par des photographies prises par Louis Sclavis et tout part d'elles. En cela, elles sont ces photos inductrices du titre.

Elles apparaissent pour la plupart agrandies, comme observées à la loupe, selon la logique d'une enquête dont l'enjeu reste mystérieux. A leur fixité répond une séquence qui tout au long du film est répétée, déclinée suivant différents rythmes. D'abord abstraite, la forme blanche qui s'y déploie se devine être un cygne. À cela s'ajoutent les fragments d'un texte, défilant disséminés en l'espace de l'écran. Ils sont des résidus de Mimique, écrit par Stéphane Mallarmé. Le plan du cygne, d'influence mallarméenne lui aussi, se réfère autant à la danse serpentine de Loïe Fuller qu'au poème Le vierge, le vivace et le bel aujourd'hui. Tout opère par ricochets, les photos conduisant au cygne conduisant au texte, conduisant le film vers une quête du blanc – dernier ricochet vers une hantise littéraire du XIXe siècle, de l'Ultima Thulé fantasmé par Edgar Allan Poe dans ses Aventures d'Arthur Gordon Pym à la blancheur de Moby Dick d'Herman Melville.

The film is constructed from three narrative layers operating in palimpsest.

It all starts with photographs taken by Louis Sclavis and everything starts from them. In this, they are these inductive photos of the title.

They appear for the most part enlarged, as if observed with a magnifying glass, according to the logic of an investigation whose stakes remain mysterious. To their fixity responds a sequence which is repeated throughout the film, declined according to different rhythms. At first abstract, the white form that unfolds there guesses to be a swan. To this are added the fragments of a text, scrolling, disseminated in the space of the screen. They are residues of Mimesis, written by Stéphane Mallarmé. The shot of the swan, also of Mallarméan influence, refers as much to Loïe Fuller’s serpentine dance as to the poem The Virgin, Vivacious and Lovely Today. Everything operates in ricochets, the photos leading to the swan leading to the text, leading the film towards a quest for white – last ricochet towards a 19th century literary obsession, of the Ultima Thule fantasized by Edgar Allan Poe in his Narratives of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket to the whiteness of Moby Dick by Herman Melville.

Les photos inductrices (Deuxième partie)Inductive Photos (Part One)

Création de Louis Sclavis et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film HDV et Super-8 (numérisé), Couleur, 18 min, 2012

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 et LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création by Louis Sclavis and Fabrice Lauterjung

HDV Film, black-and-white, 22 min, 2011

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 and LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création de Louis Sclavis et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film HDV et Super-8 (numérisé), Couleur, 18 min, 2012

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 et LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création by Louis Sclavis and Fabrice Lauterjung

HDV Film, black-and-white, 22 min, 2011

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Le Bureau 31 and LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Le film commence là où le premier volet s'était interrompu, par un écran blanc, avant de progressivement laisser place à des formes de plus en plus distinctes, lesquelles mènent aux mains d'une femme aveugle lisant un texte en braille. Dès lors, tout le film suit le parcours que cette lecture induit. Des mots éparses et phrases incomplètes se donnent à lire – il s'agit d'extraits d'une des lettres qu'écrivait Denis Diderot à Sophie Volland, celle datée du 10 juin 1759 ; les photos de Louis Sclavis apparaissent creusées par des recadrages cherchant à extraire d'elles d'autres situations narratives – paysages enneigés vus d'un train, gare et silhouette d'homme, silhouette de femme, ancienne salle de cinéma aux fauteuils vides, clairière, ciel rouge, forêt, route et neige encore. La narration procède par apparitions, comme si, ce que ces mains lisaient au contact des aspérités du papier, se traduisait en instants photographiques et phrases fragmentées.

The film is constructed from three narrative layers operating in palimpsest.

It all starts with photographs taken by Louis Sclavis and everything starts from them. In this, they are these inductive photos of the title.

They appear for the most part enlarged, as if observed with a magnifying glass, according to the logic of an investigation whose stakes remain mysterious. To their fixity responds a sequence which is repeated throughout the film, declined according to different rhythms. At first abstract, the white form that unfolds there guesses to be a swan. To this are added the fragments of a text, scrolling, disseminated in the space of the screen. They are residues of Mimesis, written by Stéphane Mallarmé. The shot of the swan, also of Mallarméan influence, refers as much to Loïe Fuller’s serpentine dance as to the poem The Virgin, Vivacious and Lovely Today. Everything operates in ricochets, the photos leading to the swan leading to the text, leading the film towards a quest for white – last ricochet towards a 19th century literary obsession, of the Ultima Thule fantasized by Edgar Allan Poe in his Narratives of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket to the whiteness of Moby Dick by Herman Melville.

Les photos inductrices (Troisième partie)Inductive Photos (Part Three)

Création de Louis Sclavis et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film HDV et Super-8 (numérisé), N&B et Couleur, 19 min, 2013

Musique : Louis Sclavis, Vincent Courtois

Production : Le Bureau 31 et LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création by Louis Sclavis and Fabrice Lauterjung

HDV Film and Super-8 film digitized, black-and-white and Color, 19 min, 2013

Music : Louis Sclavis, Vincent Courtois

Production : Le Bureau 31 and LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création de Louis Sclavis et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film HDV et Super-8 (numérisé), N&B et Couleur, 19 min, 2013

Musique : Louis Sclavis, Vincent Courtois

Production : Le Bureau 31 et LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Création by Louis Sclavis and Fabrice Lauterjung

HDV Film and Super-8 film digitized, black-and-white and Color, 19 min, 2013

Music : Louis Sclavis, Vincent Courtois

Production : Le Bureau 31 and LUX Scène Nationale de Valence

Après la première partie placée sous le « cygne » de Mallarmé, d'une deuxième, plus colorée, qui progressait au rythme des mains d'une aveugle lisant en braille une lettre de Diderot, la troisième et dernière partie nous fait entrer dans une série d'images en noir et blanc : d'abord une forêt d'où s'enfuit un vol d'oiseaux, des formes abstraites qui s'avèrent être des visages, puis une ronde d'enfants dansant autour d'un feu. En contrepoint rythmique et pictural apparaissent les images mouvantes quoique saccadées d'une femme vêtue d'une robe rouge. Elle danse, bientôt rejointe par un homme portant un costume noir. Quelques phrases et mots isolés défilent en rythmes variés, comme possible traces résiduelles d'un éclatement du texte dont elles furent prélevées – Éloge du maquillage de Charles Baudelaire. Progressivement, les motifs en couleur et ceux en noir et blanc se rencontrent et se mélangent.

After the first part placed under Mallarmé’s “swan”, a second, more colourful, which progressed to the rhythm of the hands of a blind woman reading a letter from Diderot in Braille, the third and final part takes us into a series images in black and white: first a forest from which flies a flight of birds, abstract shapes that turn out to be faces, then a round of children dancing around a fire. In rhythmic and pictorial counterpoint appear the moving, though jerky images of a woman in a red dress. She is dancing, soon joined by a man wearing a black suit. A few isolated sentences and words scroll in varied rhythms, as possible residual traces of a bursting of the text from which they were taken – In Praise of makeup by Charles Baudelaire. Gradually, the patterns in colour and those in black and white meet and blend.

Dans les reflets de l'ombre...In the Shadow’s Reflection

Création d’Olivier Massot et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 24 min, 2009

Musique : Olivier Massot

Interprété par le Quatuor Johannes

Production : Musée des Confluences, Lyon

Creation by Olivier Massot and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 1h40, 2009

Music : Olivier Massot

Interpreted by Le Quatuor Johannes

Production : Musée des confluences, Lyon

Création d’Olivier Massot et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 24 min, 2009

Musique : Olivier Massot

Interprété par le Quatuor Johannes

Production : Musée des Confluences, Lyon

Creation by Olivier Massot and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 1h40, 2009

Music : Olivier Massot

Interpreted by Le Quatuor Johannes

Production : Musée des confluences, Lyon

Commande du Musée des Confluences de Lyon, en partenariat avec le Planétarium de Vaulx-en-Velin, à l’occasion d’une conférence sur l’exobiologie.

This work was commissioned by the Musée des Confluences in Lyon in partnership with the Planetarium of Vaulx-en-Velin for a conference on exobiology. One at a time, scientists speak onstage, expounding viewpoints and analyses. Their talks are interspersed with three musical moments played by a string quartet. The music unfolds in search of a motif, and gradually fuses with the short film sequences being projected. On a second screen, like a continuous décor-in-motion, a film depicts an attempt to solve a puzzle. The first pieces are placed. Hands falter, start over, rectify… The image gradually takes shape before our eyes.

I East 70th Street, NY1 East 70th Street, NY

Film mini DV, Couleur, 42 min, 2008

Saxophone : Patrice Foudon, Jean-Michel Pirollet

Clavier, électroacoustique : Philippe Madile

Mini DV film, Color, 42 min, 2008

Saxophone : Patrice Foudon, Jean-Michel Pirollet

Keyboards, electroacoustic : Philippe Madile

Film mini DV, Couleur, 42 min, 2008

Saxophone : Patrice Foudon, Jean-Michel Pirollet

Clavier, électroacoustique : Philippe Madile

Mini DV film, Color, 42 min, 2008

Saxophone : Patrice Foudon, Jean-Michel Pirollet

Keyboards, electroacoustic : Philippe Madile

Trois musiciens, deux saxophonistes et un claviériste électroacousticien, jouent sur scène tandis qu’une projection a lieu. Les images sont constituées de plans de New York tournés en 1970 et 2003. En surimpression s’inscrivent des textes – descriptions ekphrastiques de quatre peintures de James Mc Neill Whistler exposées à la Frick Collection, au I East 70th Street, à New York.

Three musicians, two on saxophone and one on electroacoustic keyboard, play onstage while images are screened. The shots are of New York in 1970 and 2003. Texts are superimposed over the images – ekphrastic descriptions of four paintings by James McNeill Whistler on display at the Frick Collection, located 1 East 70th Street, New York.

IntégrationIntégration

Film HDV, Couleur, 10 min, 2014

Création : Sphlax / Badema, Fabrice Lauterjung

Musique : Naagré — Sphlax / Badema

Production : Athos Productions

Film HDV, Couleur, 10 min, 2014

Création : Sphlax / Badema, Fabrice Lauterjung

Musique : Naagré — Sphlax / Badema

Production : Athos Productions

Film HDV, Couleur, 10 min, 2014

Création : Sphlax / Badema, Fabrice Lauterjung

Musique : Naagré — Sphlax / Badema

Production : Athos Productions

Film HDV, Couleur, 10 min, 2014

Création : Sphlax / Badema, Fabrice Lauterjung

Musique : Naagré — Sphlax / Badema

Production : Athos Productions

Fugue pour piano et caméra : La valse de JeanneFugue for Piano and Camera : Jeanne's waltz

Création de Moko et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 5 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Creation by Moko and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 40 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Création de Moko et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 5 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Creation by Moko and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 40 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Sur scène, un pianiste joue avec son moi projeté. Lui et son "double" interagissent selon le principe musical de la fugue. Une rencontre entre une copie et son original, qui enrichissent la composition de manière interdépendante.

Onstage, a pianist plays together with his screened self. He and his “double” interact according to the musical principle of the fugue. An encounter between a copy and its original, co-dependently fleshing out the composition.

Fugue pour piano et caméra : The dreamcatcherFugue for Piano and Camera : The dreamcatcher

Création de Moko et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 5 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Creation by Moko and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 40 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Création de Moko et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 5 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Creation by Moko and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 40 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Fugue pour piano et caméra : Un train pour TashkentFugue for piano and camera: A train to Tashkent

Création de Moko et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 7 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Creation by Moko and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 40 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Création de Moko et Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 7 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Creation by Moko and Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 40 min, 2005

Piano : Jérôme Margotton

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Poire, prune, Etc.Poire, prune, Etc.

Film mini DV, Couleur, 14 min, 2011

Film mini DV, Couleur, 14 min, 2011

Film mini DV, Couleur, 14 min, 2011

Film mini DV, Couleur, 14 min, 2011

Dérive / ArchiveDérive / Archive

Co-réalisation : Mélodie Blanchot, Loïc Bontems, Romain Descours, Cécile Verchère

Film Mini DV, N&B et Couleur, 28 min, 2004

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Co-direction : Mélodie Blanchot, Loïc Bontems, Romain Descours, Cécile Verchère

Mini DV film, Color and black-and-white, 28 min, 2004

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Co-réalisation : Mélodie Blanchot, Loïc Bontems, Romain Descours, Cécile Verchère

Film Mini DV, N&B et Couleur, 28 min, 2004

Musique : Louis Sclavis

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Co-direction : Mélodie Blanchot, Loïc Bontems, Romain Descours, Cécile Verchère

Mini DV film, Color and black-and-white, 28 min, 2004

Music : Louis Sclavis

Production : Rhino Jazz Festival

Relecture contemporaine de la psychogéographie situationniste, construite sur la notion de territorialité. Le film, intégralement composé d’images d’archives de la ville de Saint-Étienne, cherche à tisser un réseau de relations (formelles, symboliques, rythmiques,...) mettant à nu ce qui, en l’archive, excède la simple fonction informative et devient un outil mnémonique.

Contemporary reinterpretation of Situationist Psychology, constructed on the notion of territoriality.

The film, entirely composed of archive images of the city Saint-Étienne, weaves a network of relationships (formal, symbolic, rhythmic,…), exposing the aspect of archives that goes beyond the purely informative function and becomes a mnemonic device.

Salle N°18Room n°18

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 14 min, 2004

Acteurs : Anthony Liébault, Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 14 min, 2004

Actors : Anthony Liébault, Fabrice Lauterjung

Film Mini DV, Couleur, 14 min, 2004

Acteurs : Anthony Liébault, Fabrice Lauterjung

Mini DV film, Color, 14 min, 2004

Actors : Anthony Liébault, Fabrice Lauterjung

C’est l’histoire d’un champ/contrechamp. Deux œuvres se font face : Épisode de la retraite de Russie de Nicolas Toussaint Charlet et Dernières paroles de l’empereur Marc Aurèle d’Eugène Delacroix. Entre, face au Delacroix, deux personnes, dont l’une en fait la description tandis que l’autre, non voyante, l’écoute. Dans cette parole est désigné l’enjeu du face à face à l’épreuve des peintures : la chute de deux empires (napoléonien et romain).

The tale of a shot/countershot. Two paintings face one another: Episode of the Retreat from Russia by Nicolas Toussaint Charlet and Last Words of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius by Eugène Delacroix. In between them are two people facing the Delacroix, one describing it while the other, who is blind, listens. The words convey the face-to-face interplay of the paintings: the fall of two empires (Napoleonic and Roman).

Miroir VacantVacant Mirror

Film Mini DV, Noir & blanc et Couleur, 5 min, 2003

Mini DV film, black-and-white and Color, 5 min, 2003

Film Mini DV, Noir & blanc et Couleur, 5 min, 2003

Mini DV film, black-and-white and Color, 5 min, 2003

Miroir Vacant est composé de plans mettant en scène le rapport à l’altérité à travers l’image spéculaire. Le film est une double projection (simultanée) sur deux écrans. Le dispositif provoque un dialogue entre les séquences ; d’abord autour d’analogies formelles basées sur une inversion optique donnant l’illusion d’une projection « en miroir », puis, cette illusion se brisant, des incohérences formelles entraînent le film vers des analogies narratives. Ainsi plutôt qu’une double projection, il s’agit de deux films projetés côte à côte, indissociables l’un de l’autre et s’interpénétrant. La fonction gémellaire du dispositif insiste sur l’indispensable complémentarité des deux écrans, et sur l’irrévocable isolement que suscitent les images.

Vacant Mirror is made up of shots depicting the relationship to otherness through the specular image. The film is a double projection (simultaneous) on two screens. The process provokes a dialogue between the sequences; first around formal analogies based on an optical inversion giving the illusion of a “mirrored” projection, then, this illusion shattering, formal inconsistencies lead the film towards narrative analogies. So rather than a double projection, these are two films screened side by side, inseparable from each other and interweaving. The twin function of the process emphasizes the indispensable complementarity of the two screens, and the irrevocable isolation that the images provoke.

Signe : NaufrageSign: Shipwreck

Film Super-8 (numérisé) et Mini DV, Couleur, 4 min, 2003

Super-8 film digitized and Mini DV, Color, 4 min, 2003

Film Super-8 (numérisé) et Mini DV, Couleur, 4 min, 2003

Super-8 film digitized and Mini DV, Color, 4 min, 2003

Entrelacement de deux récits. Le premier est celui d’une fillette, de dos face à la mer, filmée en un unique plan ralenti au point qu’il semble être une seule image, fixe. Pourtant l’écume progresse et la fillette bouge, très lentement. Le second ressemble à un vieux film de vacances, une série de choses sans importance filmées sans avoir été préméditées : une station balnéaire, la mer, un bateau, des palmiers, un cerf-volant, une plage, des rochers, l’écume, la nuit, des arbres au vent, des collines, une femme de dos et sa chevelure blonde au vent, les vagues.

Two intertwining stories. The first involves a little girl, filmed from behind, facing the sea, in a single slow-motion shot, giving the impression of a still image. However, very slowly the sea-foam shifts and the girl moves. The second resembles an old holiday film, a series of insignificant unplanned things: a beach resort, the sea, a boat, palm trees, a kite, a beach, rocks, foam, night, windswept trees, hills, a woman seen from behind, her blond hair blowing in the wind, waves.

artpress - Chroniques cinéma

Par Fabrice Lauterjung

— Corps médicaux / Médical Bodies, artpress n°502, sept. 2022

— Ce n’est qu’un jeu / Just Gaming, artpress n°501, été 2022

— Une histoire adjacente / An Adjacent History, artpress n°499, mai 2022

— Serge Daney : correspondance amoureuse / Love Letters, artpress n°497, mars 2022

— Sans bord ni cadre / With Neither Edge Nor Frame, artpress n°495, jan. 2022

— « Long live cinema ! » / Intimist Wandering, artpress n°493, nov. 2021

Par Fabrice Lauterjung

— Corps médicaux / Médical Bodies, artpress n°502, sept. 2022

— Ce n’est qu’un jeu / Just Gaming, artpress n°501, été 2022

— Une histoire adjacente / An Adjacent History, artpress n°499, mai 2022

— Serge Daney : correspondance amoureuse / Love Letters, artpress n°497, mars 2022

— Sans bord ni cadre / With Neither Edge Nor Frame, artpress n°495, jan. 2022

— « Long live cinema ! » / Intimist Wandering, artpress n°493, nov. 2021

Corps médicaux – Médical Bodies

artpress n°502, sept. 2022

Lundi 23 mai 2022, Cannes, Théâtre Croisette: projection du film De humani corporis fabrica de Lucien Castaing-Taylor et Véréna Paravel, en première mondiale à la Quinzaine des réalisateurs de Cannes. Bâle, juin 1543 : parution du « premier ouvrage d’anatomie fondé sur l’observation et la dissection », De humani corporis fabrica (La fabrique du corps humain) de l’anatomiste flamand André Vésale. Un mois auparavant, à Nuremberg, était publié le De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Des révolutions des orbes célestes) de Nicolas Copernic. Le livre de Vésale repose sur une observation méthodique et illustrée du corps humain et de ses mécanismes. Fort de ses compétences en médecine, Vésale en signe le texte. Les illustrations sont, elles, exécutées par des artistes élèves du Titien, dont le principal, Jean de Calcar. Science et art se rencontrent et se nourrissent l’une l’autre au bénéfice du savoir. De son côté, Copernic théorise les premiers éléments d’un décentrement réfutant le géocentrisme de Ptolémée au profit d’un système héliocentrique. Si tout semble attester une parfaite concomitance entre les deux ouvrages, il ne doit pas être négligé, selon le philosophe Georges Canguilhem, qu’« en 1543, quand Copernic proposait un système où la terre natale de l’Homme n’était plus la mesure et la référence du monde, Vésale présentait une structure de l’Homme où l’Homme était lui-même, et lui seul, sa référence et sa mesure. [1] » Vésale fait de l’homme un centre propice à son raisonnement anatomique tandis que Copernic le met en orbite et en révolution. Néanmoins, mécaniques céleste et biologique se répondent – l’immensément grand et lointain rencontre l’intimité du très proche – et la croyance en une autorité supérieure et omnipotente vacille – l’incommensurable devient mesurable. Ainsi le monde perd-il son centre et se désacralise : il n’est plus la prérogative de Dieu, ni l’Homme – qui désormais prend en main ses origines et son destin – son privilège. Et c’est d’ailleurs par la main que l’Homme de Vésale délivre ses mystères : une main qui écrit, qui dessine et, surtout, qui dissèque. Une main garante d’une authentification de ce que les yeux perçoivent. Aussi l’observation des corps se fait-elle autant par la vue que par le toucher – ce que Jean Riolan le fils, un siècle après Vésale, synthétisera par la belle formule de « main oculaire ».

De ce couple oculo-manuel, les outils sont une extension dont l’e cience ne cessera de s’amplifier et spectaculairement s’accélérer à la fin du 19e siècle. C’est en 1895 – année de naissance du cinématographe Lumière – que Wilhelm Röntgen découvre les rayons X qui fascinent les médecins comme le grand public. Notons que la première radiographie fut celle d’une main, et pas n’importe laquelle, puisqu’elle appartenait à Bertha Röntgen, l’épouse du physicien. Image paradoxale et, corrélativement, forte de sens, en tant que cette découverte permettait, précisément, « d’épier le fonctionnement des organes à l’intérieur du corps » sans avoir à le « manipuler ». Aussi la main, sans totalement disparaître des procédés d’observation, se fera- t-elle de plus en plus discrète, progressivement suppléée par de nouveaux outils. Dès lors, « le malade ou plutôt son corps circule entre des machines que desservent des manipulateurs muets, le regard capté par l’appareil. Silence, on tourne... [2] » Après les rayons X, l’imagerie de la transparence, caractéristique de la médecine du 20e siècle, accroît l’exploration des zones longtemps restées inobservables sur le corps des vivants. En 1934, Irène et Frédéric Joliot-Curie ouvrent la voie de la médecine nucléaire et, 22 ans plus tard, la première scintigraphie a lieu. L’échographie naît au début des années 1950, la tomodensitométrie (scanner), ainsi que l’IRM, dans les années 1970. La miniaturisation des dispositifs optiques (endoscopiques) complète le panel, permettant «une spéléologie de la vie des organes [creux]». Et pendant ce temps, les recherches et découvertes sur le génome humain progressent et façonnent de nouvelles images, plus passe-murailles encore et toujours plus abstraites, manifestant l’ambivalence d’une imagerie « à la fois double du réel et fondamental leurre, porteur d’information et d’équivoque entre l’objet donné et construit. [3]» […]

1. Georges Canguilhem, « L’homme de Vésale dans le monde de Copernic : 1543 », Études d’histoire et de philosophie des sciences, Vrin, 1989 (1968), republié en 1991 par Les Empêcheurs de penser en rond.

2. Anne-Marie Moulin, « Le corps face à la médecine », Jean-Jacques Courtine (dir.), Histoire du corps,

3. Les mutations du regard. Le 20e siècle, Seuil, « Points », 2015 (2006). 3 Ibid.

[EN]

Monday, May 23rd, 2022, Cannes, Théâtre Croisette: screening of the film De humani corporis fabrica by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, world premiere at the Cannes Directors’ Fortnight. Basel, June 1543: publication of the “first book of anatomy based on obser- vation and dissection,” De humani corporis fabrica (Of the Structure of the Human Body) by the Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius. A month earlier, De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) by Nicolaus Copernicus had been published in Nuremberg. Vesalius’ book is based on a methodical, illustrated observation of the human body and its mechanisms. Vesalius signed the text on the strength of his medical skills.The illustrations were executed by artists who had studied underTitian, including his main student, Jean de Calcar. Science and art met and informed each other for the benefit of knowledge. For his part, Copernicus theorised the first elements of a decentring which refuted Ptolemy’s geocentric cosmology in favour of a heliocentric system. Although there appears to be a perfect concomitance between the two works, we must not forget, according to the philosopher Georges Canguilhem, that “in 1543, when Copernicus proposed a system in which man’s native land was no longer the measure and the reference of the world, Vesalius presented a human structure in which man himself was the sole reference and measure.” [1]

Vesalius made man a centre conducive to his anatomical reasoning, whereas Copernicus put him in orbit and in revolution. Nevertheless, celestial and biological mechanics were symmetrically positioned— the large and distant immensity encountered the intimacy of the immediate closeness—and belief in a superior and omnipotent authority wavered—the immeasurable became measurable.The world thereby lost its centre and became demystified: it was no longer the prerogative of God, nor was Man— who henceforth took charge of his origins and his destiny—its privilege. And it was also by means of the hand that Vesalius’ Man broke free of his mysteries: a hand that wrote, drew, and above all, dissected. A hand that guaranteed the authentication of what the eyes perceived. The observation of bodies was therefore carried out by sight as much as by touch—something that Jean Riolan the Younger, a century after Vesalius, synthesised with the beautiful formula of the “ocular hand.”

Tools became an extension of this oculo-manual couple, whose efficiency continued to grow before dramatically accelerating at the end of the nineteenth century. Wilhelm Röntgen discovered the X-rays that fascinated doctors and the general public in 1895—the year of the birth of the cinematographer Lumière. We note that the first X-ray was that of a hand, and not just any hand, since it belonged to Bertha Röntgen, the physicist’s wife. This was a paradoxical and powerful image, since the discovery made it possible to “observe the functioning of organs within the body” without having to “manipulate it.” Without completely disappearing from the observation process, the hand therefore became increasingly discreet, gradually supplemented by new tools. From then on, “the patient, or rather his body, circulated between machines served by mute manipulators, their gaze trained on the apparatus. Quiet on set...” [2] After X-rays, transparency-based imaging, characteristic of twentieth-century medicine, facilitated the exploration of areas which had long been unobservable in the bodies of living things. In 1934, Irene and Frédéric Joliot-Curie paved the way for nuclear medicine, and the first scintigraphy took place 22 years later. Ultrasound was born in the early 1950s, followed by computed tomography (CT) and MRI in the 1970s.The miniaturisation of optical devices (endoscopy) completed the array of tools, enabling “a speleology of the life of [hollow] organs.” At the same time, research and discoveries about the human genome were underway, shaping new images, pushing boundaries, becoming increasingly abstract, manifesting the ambivalence of imaging that was “both a copy of reality and a fundamental illusion, conveying both information and ambiguity between the given and the constructed object.”[3]

1. Georges Canguilhem, “L’homme de Vésale dans le monde de Copernic: 1543,” Études d’histoire et de philosophie des sciences, Vrin, 1989 (1968).

2. Anne-Marie Moulin, “Le corps face à la médecine,” Jean-Jacques Courtine (eds.), Histoire du corps,

3. Les mutations du regard. Le 20e siècle, Seuil, “Points”, 2015 (2006). 3 Ibid.

Translation: Juliet Powys

————

Ce n’est qu’un jeu – Just Gaming

artpress n°501, été 2022

Dimanche 23 mai 1999, cérémonie de clôture de la 52e édition d’un festival de Cannes dont le palmarès restera comme l’un des plus controversés. En cause, une palme d’or – Rosetta des frères Dardenne – jugée trop « sociale », trop « réaliste », trop « documentaire », bref, pas assez « glamour ». En cause également, le prix du meilleur scénario pour le Moloch d’Alexandre Sokourov, film relatant les derniers jours d’un Adolf Hitler sans charisme, humain trop humain, inadmissible donc. C’est bien connu, les tyrans sont des êtres exclus de l’espèce humaine et Hannah Arendt n’a jamais rien écrit sur la banalité du mal... En cause, sur- tout, les prix d’interprétations féminine et masculine décernés à des non-professionnels, Séverine Caneele et Emmanuel Schotté, actrice et acteur d’un film de Bruno Dumont, l’Humanité – auréolé du grand prix du jury, qui plus est. Verdicts intolérables pour les « professionnels de la profession». Que leurs pronostics aient été contredits n’était pas le plus scandaleux, une simple piqûre à l’amour propre. Le scandale était d’une autre nature, comparable au lieutenant Columbo venant faire intrusion chez les puissants jusqu’à les faire tomber de leur piédestal. Il y avait scandale à élire des films à l’âpreté contraire aux désirs œcuméniques consistant à réunir ambitions auteuristes et satisfaction du « grand public ». Surtout, il y avait scandale à voir entrer – par la grande porte – des acteurs « de circonstance » au sein d’une famille manifestement peu encline à voir débarquer de nouveaux membres. L’usine à rêves ne faisait plus tellement rêver, dès lors qu’une authentique ouvrière – ce qu’était Séverine Caneele avant que Dumont ne la repère – et un chômeur, anciennement militaire – Emmanuel Schotté, en l’occurrence –, avaient eu l’outrecuidance de jouer à être autre chose qu’eux-mêmes, et qu’un jury avait, de surcroît, osé les récompenser. Autrement dit, les breloques ne se décernent pas aux gueux. Ce dont témoignaient ces réactions abondamment relayées par la presse dénotait une évidente arrogance de classe mais sous-entendait aussi la peur d’une altérité. Si les histoires d’opprimés n’ont, au cinéma, jamais manqué, il était préférable que ceux-ci se restreignent à être des images sur un écran mais jamais ne le franchissent. Paradoxe de cet écran qui, bien que faisant office de fenêtre ouverte sur le monde et ses malheurs, nous en sépare et nous en préserve. […]

[EN]

The closing ceremony of the 52nd edition of the Cannes Film Festival was held on Sunday, May 23rd, 1999. The list of winners remains one of the most controversial to date. Rosetta, by the Dardenne brothers, which won the Palme d’Or, was considered to be too “social,” too “realistic,” too “documentary”, in short, not “glamour” enough.

Also controversial was the winner of Best Screenplay: Moloch by Alexandre Sokurov, a film about the last days of an Adolf Hitler whose portrayal was seen as being without charisma, all too human, and therefore inadmissible. Because of course, we all know that tyrants are not part of the human race and that Hannah Arendt never wrote anything about the banality of evil... Perhaps the most contested awards were the prizes for Best Actress and Actor, which were bestowed on non-professionals, Séverine Caneele and Emmanuel Schotté, the stars of L’Humanité, a film by Bruno Dumont which won the Jury Prize. This was intolerable for the “professionals of the pro- fession.” The most scandalous thing was not that their predictions had been refuted, that was merely a slight to their pride. The scandal was of a different nature, comparable to Lieutenant Columbo coming to intrude amongst the powerful and making them fall from their pedestal. It was scandalous to award films whose harshness was at odds with the ecumenical desire to combine auteur ambitions and the satisfaction of the “general public.” Above all, it was scandalous to see actors “of circumstance” enter— through the main door, no less— into a family which was obviously not inclined to welcome new members. The dream factory was no longer such a dream now that an authentic worker—which is what Séverine Caneele was before Dumont spotted her—and an unemployed former soldier—Emmanuel Schotté—had had the arrogance to play at being something other than themselves, and that a jury had dared to award them. In other words, honours should not be heaped upon paupers.These reactions, which were widely reported in the press, revealed an obvious class arrogance but also an implied fear of otherness. Whilst the stories of the oppressed have never been lacking in the cinema, it was deemed preferable for them to remain restricted to images on a screen, without ever crossing it. Such is the paradoxical nature of the screen which, whilst acting as a window to the world and its misfortunes, also separates and preserves us from it. […]

Translation: Juliet Powys

————

Une histoire adjacente – An Adjacent History

artpress n°499, mai 2022

26 janvier 2022. Sur des écrans répartis aux quatre coins du monde, de nombreuses personnes se sont connectées sur le site de l’IFFR (Festival international du film de Rotterdam) pour découvrir la sélection de la 51e édition. Contraintes sanitaires néerlandaises oblige, cette année encore, hélas, le festival se tient hors les murs des salles a liées, mais entre les murs des domiciles de celles et ceux que l’on peine à nommer encore festivaliers. Lentement mais sûrement, le cinéma serait-il en train d’opérer sa mue et les films de s’exiler vers des espaces domestiques ? Symptôme aigu du « monde d’après » ou bénigne contrariété passagère vouée à tomber en désuétude sitôt le « monde d’avant » retrouvé ?

Comme dans bien d’autres domaines, l’après-Covid était déjà contenu dans l’avant, et cela faisait belle lurette que le « cinéma » se pratiquait, en partie, chez soi. S’il ne fait aucun doute que la projection en salle reste la condition idéale pour qu’un film soit vu, encore faut-il être en présence d’un public sachant concentrer son attention en direction de l’écran. Qu’il sache se faire oublier, donc ; sans quoi la projection se transforme vite en un moment pénible – ce qui, a priori, disqualifie les lieux pratiquant le mélange des genres cinématographiques et « culinaires ». Parole de puriste ? Peut-être. Mais il en va d’une exigence à ne pas souhaiter confondre art et divertissement, à ne pas se résigner de voir une œuvre réduite à n’être qu’un produit consommable parmi d’autres. Serait-ce dire qu’un film ayant migré sur support vidéo aurait nécessairement perdu ses propriétés cinématographiques ? Qu’étant devenu achetable et regardable à loisir – le rituel de sa projection en salle disparu –, il serait, au mieux, une imparfaite copie, au pire, incapable de restituer ce dont l’original était fait ? Depuis l’arrivée et l’essor de ces supports – la cassette VHS (Video Home System) d’abord, à la fin des années 1970, le DVD (Digital Versatile Disc) ensuite, à la fin des années 1990, et une quinzaine d’année plus tard, quoique plus marginal, le Blu-Ray –, la relation que nous entretenons au cinéma s’est trouvée bouleversée, jusqu’à connaître aujourd’hui une prolifération des canaux de diffusion avec internet. […]

[EN]

January 26th, 2022. On screens all around the world, people logged on to the IFFR website (International Film Festival Rotterdam) to discover the selection of the 51st edition. Once again, unfortunately, the Dutch health constraints obliged the festival to take place outside the walls of the affiliated cinemas, within the homes of those whom we now struggle to define as festival-goers. Slowly but surely, is cinema in the process of moving, and films being exiled towards domestic spaces? Is this an acute symptom of the “world after,” or a benign and transient annoyance doomed to disappear as soon as the “before times” resume? As in many other fields, the post-COVID era was already contained in the past, since “cinema” has long been practised, in part, at home. Although there is no doubt that a theatrical screening remains the ideal setting in which to appreciate a film, this nevertheless requires the presence of an audience that can focus its attention on the screen. That are able to forget themselves; otherwise the projection can quickly turn into a nuisance—which effectively disqualifies venues which practice a mixture of the cinematographic and the “culinary” genres. A purist approach? Possibly. But it is important not to confuse art and entertainment, not to resign oneself to seeing works of art reduced to the status of consumer products amongst others. Is this to say that a film, having migrated to the medium of video, necessarily loses its cinematic properties? That having become purchasable and watchable at leisure — in the absence of the ritual of its theatrical projection—it is, at best, an imperfect copy, at worst, incapable of restoring the essence of the original? Since the arrival and development of these media—the VHS (Video Home System) cassette first, in the late 1970s, the DVD (Digital Versatile Disc) in the late 1990s, and some 15 years later, more marginally, Blu-Ray—our relationship to the cinema has been turned upside down, to the extent that there is now is a proliferation of distribution channels online. […]

Translation: Juliet Powys

————

Serge Daney : correspondance amoureuse – Love Letters

artpress n°497, mars 2022

Lyon, 14 décembre 2021, librairie de l’institut Lumière. En haut d’un rayonnage de livres est disposé, sur un présentoir, le numéro 120 d’une revue mythique : Trafic. Ce numéro-anniversaire clôt un chapitre de trente années de textes consacrés au cinéma [1], en tant qu’il est un art, une passion, un fidèle compagnon qui nous interpelle pour nous donner des nouvelles du monde.

30 ans et un millier d’auteurs qui signèrent plus de 1500 textes, contribuant à poursuivre ce qu’avait entrepris celui qui en fut l’initiateur et co-fondateur, épaulé de Raymond Bellour, Jean-Claude Biette, Sylvie Pierre Ulmann, Patrice Rollet et l’éditeur Paul Otchakovsky-Laurens : Serge Daney. Pour qui s’aventure à écrire sur, ou plutôt, d’après le cinéma, difficile de ne pas se rappeler la fulgurance de sa plume, difficile de ne pas se référer à l’immense corpus critique qu’il a légué et, en un geste filial, essayer de mettre ses pas dans les siens, continuer d’emprunter les passages reliant écrans et pages. Écrire d’après le cinéma, c’est inévitablement circuler dans le temps – celui des films, d’une projection et de son souvenir, d’images entremêlées de sons, de récits... C’est toujours un peu refaire le film (comme certains refont le match), le revoir, mais avec des mots, et tenter de fixer sur papier des intuitions et hypothèses qui, bien souvent, furent d’abord maladroitement énoncées.

C’est échanger avec l’Histoire (et pas seulement celle des arts dont le 7e s’est abondamment nourri), qu’elle soit déjà écrite – mais à toujours mettre en mouvement – ou en train de s’écrire. Divaguer en inactuel ou, plu- tôt, de manière intempestive et ne pas tomber dans le piège d’un présent autosuffisant. Ne pas suivre frénétiquement l’actualité pour ne pas risquer d’être à la traîne et, forcément, en retard. Daney, en une belle formule, disait de certains films qu’ils étaient « à l’heure ». Or, ne sont pas nécessairement « à l’heure » les films qui nous sont contemporains. Il faut parfois « quitter les autoroutes battues et reprendre les sentiers qui bifurquent, même ceux qui ne vont nulle part ou ramènent à la case dé- part. Perdre du temps pour finir par en gagner. [2] » Sonder le passé pour mieux entrevoir le présent et savoir débusquer les œuvres du moment. Les films, les grands, parce qu’ils traversent le temps en demandent également. Aussi ne faut-il pas craindre la suggestion de Jean-Claude Biette, en ouverture du numéro 25, de les laisser dormir en nous pour les mieux « sentir doucement s’éveiller ». […]

[EN]

Lyon, 14 December 2021, Lumière Institute bookshop. At the top of a shelf of books, on a display stand, issue no. 120 of a legendary magazine: Trafic. This anniversary issue is closing a chapter of thirty years of texts devoted to cinema [1], as an art, a passion, a faithful companion that addresses us to give us news of the world. Thirty years and a thousand authors who signed more than 1,500 texts, contributing to the continuation of what was undertaken by the initiator and co-founder, Serge Daney — with the help of Raymond Bellour, Jean-Claude Biette, Sylvie Pierre Ulmann, Patrice Rollet and the editor Paul Otchakovsky-Laurens. For anyone who ventures to write about, or rather, after the cinema, it is di cult not to recall the brilliant searing power of his pen, di cult not to refer to the immense critical corpus that he has bequeathed and, in a filial gesture, to keep on following the paths that link screens and pages.

Writing after cinema inevitably means moving through time—the one of films, of a screening and its recollection, of images intertwined with sounds, of stories... It is always a bit like remaking the film (as some people replay the match), seeing it again, but in words, and trying to fix on paper intuitions and hypotheses which, very often, were initially awkwardly stated.

It’s an exchange with History (and not only the history of the arts, among which the seventh has been copiously fed), whether it is already written—but still to be set in motion—or in the process of being written.To meander through the non-current, or rather, in a spontaneous manner, and not to fall into the trap of a self-sufficient present. Not to frantically follow current events so as not to risk being left behind and, inevitably, late. Daney, within a beautiful sentence, talks about certain films being “on time”. However, films that are contemporary to us are not necessarily “on time”. It is sometimes necessary to “leave the beaten track and take the paths that branch off, even those going nowhere or leading back to a square one.To waste time in order to gain time.” [2] Probing the past to get a better glimpse of the present and knowing how to flush out the works of the moment. Films, the great ones, because they pass through time, also require this. So we shouldn’t be afraid of Jean-Claude Biette’s suggestion, in the opening of issue 25, to let them sleep in us so as to better “feel them slowly awaken”. […]

Translation: Chloé Baker

————

Sans bord ni cadre – With Neither Edge Nor Frame

artpress n°495, jan. 2022

Florence, église Santa Maria del Carmine, samedi 8 octobre 2021. Devant les peintures de Masaccio, Fillipo Lippi et Masolino de la chapelle Brancacci, une dizaine de visiteurs regardent attentivement… les écrans des tablettes numériques mises à leur disposition en guise de vidéoguide. Les fresques sont pourtant là, à quelques mètres. Pour les voir, il faut à la fois s’approcher et lever les yeux. Mais ce sera essentiellement la tête baissée à scruter les détails reproduits sur des prothèses numériques (complétées d’une paire d’oreillettes permettant d’écouter un commentaire afférent) que ces personnes, disposées à faire entorse au parcours touristique le plus couru, feront la visite.

Quoiqu’elle fût certainement motivée par une louable intention de s’instruire, l’attitude a de quoi surprendre. Pourquoi gâcher les 30 minutes autorisées (la visite ne pouvant excéder cette durée) à regarder autre chose que l’œuvre – la vraie, l’originale ?

Première hypothèse : l’accompagnement pédagogique est rassurant en tant qu’il permet d’amortir partiellement la peur de ne savoir de quoi il retourne, au risque de rendre secondaire le plaisir de contempler les qualités proprement picturales.

Deuxième hypothèse : à une époque de circulation massive d’informations et d’images, l’expérience du monde et de ses soubresauts se vit de plus en plus par procuration, ce qui a tendance à brouiller la frontière entre événement vécu ou rapporté et, conséquemment, relativiser leur différence. Aussi les quelques va-et-vient des globes oculaires entre les peintures et leurs reproductions sur tablettes participent-ils d’une sorte de vue d’ensemble où original et copie se confondent en une complémentarité didactique.

Troisième hypothèse : reprenant la belle expression de Nancy Huston (également développée dans un récent ouvrage de Johann Chapoutot), nous sommes une « espèce fabulatrice ». Aussi notre rapport au réel se noue-t-il dans l’engendrement d’une fiction, « cela ne veut pas dire qu’il n’y ait pas de faits ; cela veut dire qu’il nous est impossible d’appréhender et de relater ces faits sans les interpréter. » [1] Ce qui nous ramène à la première hypothèse et aux réconfortants récits qui accompagnent les œuvres par le truchement d’outils audiovisuels.

Avant que le cinématographe Lumière ne soit apparu et, avec lui, la projection de films sur grand écran destinée à un spectacle collectif, le kinétoscope d’Edison et Dickson permettait déjà de voir des images en mouvement. Mais c’était debout, le buste penché en avant, qu’une seule personne pouvait voir le film à travers une petite lucarne.

La télévision, dont la progressive conquête des foyers de la planète commencera au lendemain de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, serait, en quelque sorte, la version domestiquée du kinétoscope. Spectacle avant tout individuel ou vaguement collectif – rappelons-nous les mots de Günther Anders, dans le Monde comme fantôme et comme matrice (1956), qui comparait les téléspectateurs à une juxtaposition de fusillés que le tube cathodique mitraille –, elle s’est vue progressivement supplanter par de nouveaux écrans, plus petits, plus maniables, plus individuels encore. […]

1. Nancy Huston, l’Espèce fabulatrice, Actes Sud, 2008, p. 89

[EN]

Florence, Santa Maria del Carmine church, Saturday, October 8th, 2021. Facing the paintings by Masaccio, Fillipo Lippi and Masolino in the Brancacci Chapel, a dozen or so visitors look attentively... at the screens of the tablets provided for them as video guides. But the frescoes are right there, just a few meters away. To see them, you have to draw closer and look up. But it is essentially with their heads down, scrutinising the details reproduced on digital prostheses (complete with a pair of earpieces allowing them to listen to a commentary on the subject) that these people, willing to deviate from the most popular tourist route, will undertake the visit. Although no doubt motivated by a laudable intention to be informed, the attitude is surprising. Why waste the 30 minutes permitted (the visit is not allowed to exceed this length of time) looking at something other than the work—the actual, original work?

The first hypothesis: educational support is reassuring insofar as it makes it possible to partially alleviate the fear of not knowing what it is all about, at the risk of rendering the pleasure of contemplating the actual pictorial qualities secondary. Second hypothesis: in an era of massive circulation of information and images, the experience of the world and its upheavals is increasingly lived by proxy, which tends to blur the border between lived and reported events, and consequently to relativise the difference between them. The few back-and-forth movements of the eyeballs between the paintings and their reproductions on screens are part of a kind of overview in which the original and the copy merge in a didactic complementarity.

Third hypothesis: taking up Nancy Huston’s beautiful expression (also developed in a recent book by Johann Chapoutot), we are a “confabulating species”, a make-believe species of tale-tellers. Thus our relationship with reality is tied to the creation of a fiction, “I don't mean to imply that facts do not exist; only that we are unable to apprehend and transmit facts without interpreting them.” [1] This brings us back to the first hypothesis, and the comforting narratives that accompany the works via audiovisual tools.

Before the Lumière cinematograph appeared, and with it the projection of films on a large screen for collective entertainment, Edison and Dickson’s kinetoscope had already made it possible to see moving images. But it was standing bent over that only one person could see the film through a small window. Television, of which the gradual conquest of the world’s homes began in the aftermath of the Second World War, would be in a way the domesticated version of the kinetoscope. A primarily individual or vaguely collective spectacle—let us recall the words of Günther Anders, in The World as Phantom and as Matrix (1956), who compared television viewers to a juxtaposition of people shot down as if by a firing squad, machine-gunned by the cathode-ray tube—it has been progressively supplanted by new screens, smaller, more manageable, still more individual. […]

1. Nancy Huston, The Tale-Tellers: A Short Study of Humankind, McArthur Publishing, 2008.

Translation: Chloé Baker

————

« Long live cinema ! » – Intimist Wandering

artpress n°493, nov. 2021

Marseille, Théâtre de l’Odeon, 21 juillet 2021. Il était bientôt 14 heures et cela faisait plus d’une heure et demie qu’Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Grand prix d’honneur du 32ème FID Marseille, proposait à une salle comble et masquée une master classe en forme d’invitation à voyager le long d’une vie commencée aux abords d’un hôpital, à observer patients et nature environnante, à être fasciné par l’imagerie médicale et s’émerveiller devant la sculpture du vivant ; une exploration du sensible dont la traduction cinématographique donnera naissance à une trentaine de pousses – films courts et longs, complétés d’installations vidéo.

Il était bientôt 14 heures quand le cinéaste décidait d’évoquer un discours tenu quelques jours auparavant, après que son dernier opus, Memoria, a été projeté (puis récompensé du prix du jury) au festival de Cannes. Ce discours, commencé par les traditionnels remerciements d’usage, il l’avait conclu par un « Long live cinema ! » qui aurait pu n’être qu’un slogan à rajouter à ceux ponctuant, chaque année, les célèbres et médiatiques projections cannoises. Oui, ces trois mots n’auraient pu être que folklore mondain s’ils n’avaient été prononcés par le ressortissant d’une monarchie qui, à l’assertion « Longue vie », n’autorise l’accolement d’un seul et unique mot, celui de « roi ».

Apichatpong Weerasethakul venait de transgresser une des règles de son pays… Et quelques jours plus tard, en Thaïlande, la phrase avait été taguée et relayée par plusieurs médias sociaux, participant du soulèvement insurrectionnel alors en germe.

Qu’il n’y ait pas méprise, il ne s’agit pas d’investir ces trois mots d’une portée politique capable de renverser un pouvoir autoritaire. Pas plus qu’il ne faudrait croire (ou souhaiter) un film (et même une œuvre) capable d’une pareille prouesse. Souvenons-nous d’un certain Fahrenheit 9/11, palme d’or décernée par un jury présidé par un certain Tarantino, en 2004. Un film et une récompense concourant à faire chuter le président W. Bush, cependant réélu quelques mois plus tard avec une marge plus conséquente qu’elle ne le fut pour sa première investiture. Cible ratée, mais dommage collatéral, en tant que le cinéma, ici devenu arme de propagande et simple outil de communication, en plus d’avoir achoppé à défaire l’ennemi, aura temporairement suspendu son ancrage artistique pour devenir un docile produit audiovisuel au service d’enjeux avant tout états-uniens.

Si « Long live cinema ! » est une déclaration sur laquelle il semble opportun de revenir, c’est qu’elle met en lumière la dimension politique d’un cinéaste dont l’œuvre est souvent circonscrite au commode et abusif qualificatif de « poétique ». Terme fourre-tout parfois propice à désigner les films aux constructions narratives et formelles hors des sentiers battus […]

[EN]

Marseille,Théâtre de l’Odéon, July 21st, 2021. It was almost 2 p.m. and for more than an hour and a half Apichatpong Weerasethakul, winner of the Grand Prix d’Honneur of 32nd FID Marseille, had been treating a packed, masked auditorium to a master class in the form of an invitation to travel through a life begun on the outskirts of a hospital, to observe patients and the surrounding nature, to be fascinated by medical imagery and to marvel at the sculpture of of the living; an exploration of the sensory, the cinematographic translation of which would yield some thirty short films and features, complemented by video installations.

It was nearly 2 p.m. when the film-maker decided to talk about a speech he had given a few days earlier, after his latest opus, Memoria, had been screened (and then awarded the Jury Prize) at the Cannes Festival.This speech, which